The teenage girl is a tragedy—and no one takes her seriously

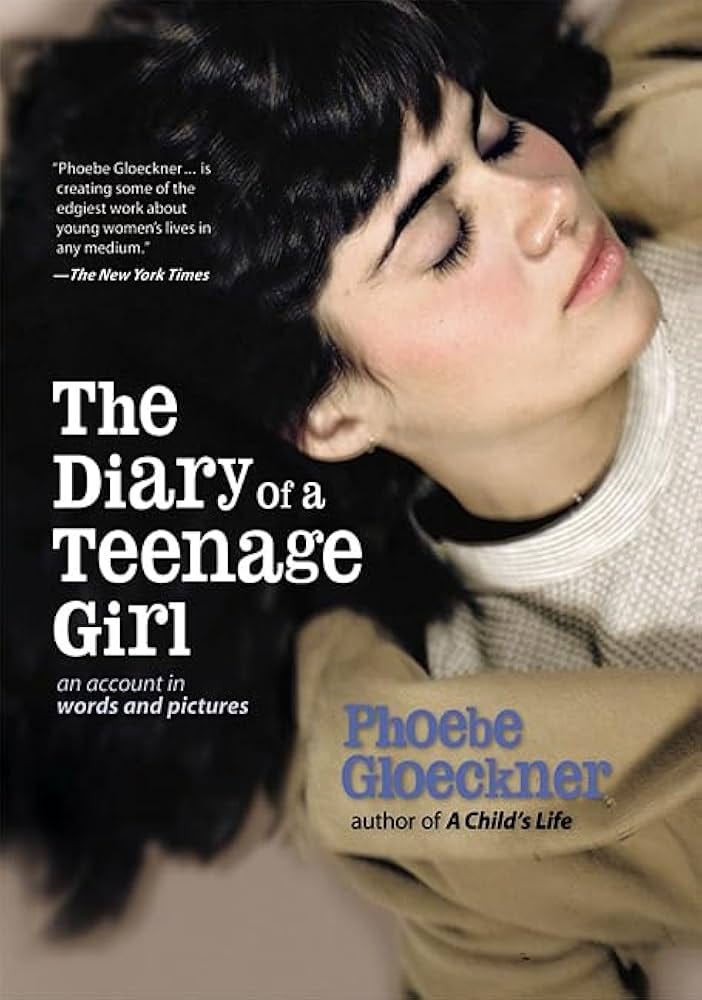

Notes on an old Hinge date, "The Diary of a Teenage Girl", and the quiet ache of wanting to be desired.

My favorite book is The Diary of a Teenage Girl. I once said that on a second date with a guy I met through Hinge. Hearing this, he let out a scoff and told me: “I really hope you didn’t just say that.”

I felt embarrassed for the rest of the night. We watched a Loch Ness monster origin story film (Water Horse: Legend of the Deep, to be exact), followed by Five Nights at Freddy’s, which I was very entertained by—and I think that enthusiasm prompted him to ghost me after that night. After that hefty double feature, we both took turns taking long drags from his janky weed pen. He got up and moved into my bedroom. I tried to follow and ended up fainting for five seconds—clutching my door handle—before I met him there. He did not notice.

It was a weird night. A couple of years have passed, and I still love The Diary of a Teenage Girl—but why did he feel so entitled to dismiss my favorite book, something that obviously meant a lot to me? And if he had no idea what the book was about, why was "teenage girl" all he needed to hear to decide it wasn’t worth taking seriously?

The teenage girl is an archetype of tragedy and longing—fetishized, dismissed, and rarely taken seriously. Her self-destruction is inevitable, yet her struggles are trivial. She is told her pain is shallow, her desires vain, her existence unserious. My date didn’t need to know what The Diary of a Teenage Girl was about to scoff at it—the words “teenage girl” alone were enough to make it laughable.

I came across The Diary of a Teenage Girl when I was 15, the same age Minnie Goetze (the protagonist) is when the story begins. The book, later adapted into a 2015 film, was both celebrated and scrutinized for its raw depiction of adolescent sexuality. It’s graphic, ugly, and raw—Minnie starts an affair with her mother’s boyfriend (Monroe), becomes a bonafide teenage delinquent, and tries drug after drug before proceeding to meth in hedonistic 1970s San Francisco. On the surface, I had literally nothing in common with her, though we were both the same age. But her writing, characterized by terrible longing and a desperate need to be desired, tore through me.

I fell in love with her the way you do with a character who articulates your pain so precisely that it feels like a wound is being exposed. It was embarrassing to recognize myself in her. But isn’t that the point of art? To feel seen, even when it’s uncomfortable?

Phoebe Gloeckner, the author of the novel, insists upon the work’s fictionality despite the main plot mirroring her own teenage experience. In fact, the book explicitly incorporates entries from her 15-year-old self’s diary—Phoebe and Minnie both had an affair with their mothers’ boyfriends. Black-and-white photographs of Gloeckner in her teenage years notably bear a striking resemblance to her drawings of Minnie. However, as she writes in the preface to the book: “This is not history or documentary or confession. [...] For this book to have real meaning, [Minnie] must be all girls, any one.”

And she is, to an extent. Minnie acutely captures the experience of being a patriarchally conditioned teenage girl. A scene from the novel that still lingers with me is when Monroe begins coaxing Minnie into sleeping with him: she complies, writing that she is “afraid to pass up the chance as [she] might never get another.”

That fear—the existential dread of being unwanted—felt shamefully familiar. Even after the man from earlier dismissed my favorite book and barely pretended to care who I was, I still slept with him. Not because I wanted to, exactly, but because it was the easiest thing to do in the moment. And if I couldn’t be respected, I could at least be desired.

We so often dismiss girls who yearn for male validation and approval as “pick-me girls.” Perhaps, as many will theorize, these girls have daddy issues or low self-esteem—coincidentally, both are traits that men tend to sexualize! I’ve always hated the term because it suggests that the desire to be chosen and validated by men is an individual flaw—something cringeworthy and pathetic—when, in reality, it’s a socially conditioned survival instinct.

Girls don’t just wake up one day desperate for male validation; they are taught that desirability is currency, and without it they are worthless. Minnie understands this on an instinctual level—she doesn’t sleep with Monroe because she wants to, but because she is terrified of what it means if she isn’t wanted at all. She is, in many ways, a case study in how girls are trained to seek validation and measure their worth through the eyes of men.

Simone de Beauvoir called this an “operation of justification.” As adolescent girls come to understand their role in patriarchal society, they develop an urgent, existential need to justify their identity in the eyes of others. How much are we worth in the masculinist economy of desire? It’s a question that informs every glance we take into the mirror, every selfie posted to Instagram—whether we know it or not.

Of course, men want to be desired too. Everyone does! But there’s a difference between wanting validation and being conditioned to believe that desirability is the foundation of your worth. The masculinist economy of desire doesn’t teach men that they cease to exist if they aren’t seen. It doesn’t tell them that their body is currency, or that their self-worth is something they must continuously earn through the gaze of others. If a man is unwanted, he is still a man. But if a woman is unwanted, she is—what, exactly? A failure? A ghost? A cautionary tale?

I think about this a lot now, from a much healthier mental space (shoutout to my therapist Mandy). And it makes me upset to think of how much better I am now that I’m in a stable, loving relationship. It’s like I only managed to unlearn this pattern of self-commodification in favor of the male gaze in my relationship with my current boyfriend. I feel seen by him constantly. And maybe that’s why I haven’t been writing about myself as much—or at all—because I already feel like someone sees me (aww! gross).

But does that mean my self-worth is still borrowed? Does every mirror, even the kindest one, warp the reflection? I want to believe I would have realized all of this on my own. Maybe with enough time and therapy, I would have. But maybe part of me still fears that self-worth isn’t something you feel—it’s something you’re given.

When I think back to my teenage self, I realize that fear has always been there. She still exists, buried beneath just four years of mental debris—a messy mix of hormones, depression, and an unhealthy attachment to Bojack Horseman. I swore to myself I wouldn’t trauma dump online, so I’ll keep this brief—but let it be known: for most of my time growing up, I hated being a girl.

My teenage self deserved so much more than how she treated and perceived herself. It breaks my heart thinking of her—how she struggled with feeling feminine, how much she wanted to be loved, how she apologized for taking up space. I feel her inside me sometimes—she’s summoned, briefly, whenever I play songs from old Spotify playlists from high school.

She still asks if we need to be chosen. I tell her we’re unlearning the lie that we ever did.

“But does that mean my self-worth is still borrowed?” is such an amazing reflection!!

Beautiful and poignant as always, def can relate to the tragedy and horror that is being a teenager girl 🙂↕️ thank you for sharing !!